We are delighted to share our interview as Othon Cinema with Peter Tscherkassky, a prominent figure in Avant-garde Cinema, with our readers at Othon Cinema. We are truly honored to have the opportunity to conduct this interview on the first anniversary of Othon Cinema. It is a privilege to share Tscherkassky’s inspiring ideas with our community and readers, shedding light on his perspective on life and cinema. First of all, we would like to thank Peter Tscherkassky, who answered all our questions sincerely and supported us throughout the interview process, and then all Othon Cinema writers who supported the interview with their questions, and Matthias Kyska who translated an interview with Tscherkassky into Turkish for us for the first time.

Welcome… Thank you very much for accepting our invitation for this interview. To start off, how have you been lately?

I have just begun working on a new film, and it’s always a challenging journey for me. I need to convince myself about the film’s structure and truly believe in it before I step into the darkroom to begin the arduous and time-consuming process of filmmaking. However, I haven’t reached that stage yet for this particular project.

Developments in the world, wars, pandemics, intricate political terrains… As a filmmaker who has been making films since the early 1980s, do you perceive any changes occurring in the world and the accompanying cinematic landscape, or is everything going on as it has been and will be?

Nothing remains the same, not even us. And art reflects this never-ending movement of all things.

Your films possess a distinct and extraordinary technical prowess, yet they never fail to evoke deep emotional and sensory responses. It’s rare to find this blend in cinema and art. How does it feel to accomplish this?

My focus has always been to create films that offer the viewer, metaphorically speaking, multiple layers during the viewing. The surface should be captivating and almost tangible, creating an intense experience. Beyond this lies the narrative, where I weave a small story intertwined with references to film history and reflections on the film medium. I view all my works as “meta-cinema”, showcasing the medium within itself.

Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine (2005)

One of the most notable techniques is layering images on top of each other. Do you believe this approach takes the audience on a reflective journey and provides a poetic experience? Can we argue that the editing style in your films presents a film that requires viewers to gather in their minds an image outline that branches out in various directions?

Condensation has always held great significance for me, alongside a heightened visual dynamic. This elucidates the strong connection between avant-garde films and poetry. Poems, too, operate by condensing the meaning of individual words. From a linguistic standpoint, this implies that the vertical paradigmatic structure carries more weight than the horizontal syntagmatic structure. Prose primarily exhibits horizontal movement, with the narrative of a novel unfolding on a horizontal plane. Conversely, a poem fixates on the individual word and all its potential meanings, encompassing its connotations. Within a poem, a word serves as a focal point for concentrated meaning, mirroring my endeavor to craft images that embody concentration and intensification. Much like our dreams, which comprise images brimming with condensed meanings.

In many of your written and video interviews, we can see that you create films like a craftsman by making great efforts physically as well as mentally. Does this situation reflect your general life practices, your perspective on cinema and the pure meaning you find there?

Analogue film was always very important to me as a pure art form. When I started making films, in late 1979, early 1980, video had emerged as a new medium of moving images, and many of my colleagues had switched to video from the then common and widely used Super 8 format. However, it was already clear to me at that time that “analogue film” and electronically produced moving images were two completely different media, if you look at them as the medium of autonomous art. Modern art is always based on the specificity of its own medium. It shows the very special possibilities offered by its own medium. At that time I also consciously decided against video and for analogue film. In order to show its completely original and unique characteristics, I produce it with a very artisanal technique. My films are handmade films, frame by frame, not just a carrier medium that can be held in your hand and processed and read only by a machine, as you can only do with a film strip.

Is it possible to consider the act of independently creating a film as analogous to the role of a creative artist in traditional art forms? Has the intimate connection between the artist and their work evolved and diverged from the foundational cultural norms within the realm of cinema? In light of this, does the fact that you, as a director, produce films single-handedly classify you as an experimental filmmaker akin to classical artists who embody the essence of their craft?

The method of production, whether collective or individual, does not impact the artistic value of a piece of art. In the visual arts, artists historically worked in studios, writers typically work alone, and in music, compositions can be created by a group or by a single musician. These distinctions do not determine whether a work is considered “traditional,” “classical,” or “contemporary.” One notable advantage of avant-garde filmmaking is the ability to maintain autonomy during the creative process.

Outer Space (1999)

You used Sidney Furie’s film “The Entity” as source material for your films “Outer Space” and “Dream Work” and why did you choose this film in particular? In other words, what criteria do you use to select a film whose elements you will later use as vocabulary for a new film?

I never consciously looked for footage, I always found something. When a film falls into my lap, I look at it and see if I can create something completely new from it, if I want to. There are several feature films in my collection that I will never utilize as they fail to spark my creativity. Conversely, I occasionally discover short film reels that serve as the catalyst for new artistic endeavors. For instance, my latest film, “Train Again,” originated from approximately three minutes of unedited footage from a railway advertisement. Over the span of three years, this small snippet evolved into a twenty-minute film of my own creation. Similarly, I was unaware of “The Entity” until I purchased it at a bargain price of $50 for a two-hour feature film. Upon viewing it, the potential for innovation within the film immediately became apparent to me.

How important is music and sound design in your filmmaking process? How do you incorporate these elements into your overall workflow and how do you divide the tasks? For instance, in Dream Work, Kiawasch Saheb Nassagh composed the film’s score. Do you plan the sound design while working on the project or do you hand over the final material to the musician and give them creative freedom?

I created the sound for “Outer Space” by combining the optical sound track with found footage images in the darkroom. Since “Dream Work,” I have collaborated with composer Dirk Schaefer from Berlin. When I hand over my films to him, they are complete. Dirk is free to develop his own ideas for the sound, and we work on scoring step by step, usually minute by minute. He provides sound scripts for short passages, which we analyze and discuss together. Sometimes his suggestions are perfect right away and sometimes I make requests, such as the musical quote from Maya Deren’s film “Meshes of the Afternoon” from Teiji Ito’s soundtrack for “The Exquisite Corpus”. During filming, I only consider soundtrack options in exceptional cases, noting them down to suggest to Dirk when they come to mind.

As you know, we now live in the age of digital film. Most cinemas show DCP copies, very few films are still shot in analogue and the younger generation has almost no connection with the analogue era. What is the challenge and meaning of this situation for directors like you who are still making films with analogue material? Do you see the transition to digital as the end of an old era?

The origin of visual arts dates back over 40,000 years when early humans utilized ash, charcoal, and chalk to create drawings in dimly lit caves. Even today, artists continue to produce contemporary pieces using charcoal and chalk. Throughout history, various new mediums have been introduced alongside existing ones, rather than replacing them. However, the moving image presents a unique challenge due to the industrial production required for analogue film’s “hardware” and “software.” If this production were to cease, analogue film would no longer be available. Despite this, there are resilient pockets within the industry that are likely to ensure the survival of analogue film for the foreseeable future.

Do you think that the technical skills needed to work with analog film are becoming less common? How does this impact young experimental filmmakers?

My experience shows me that the analogue film medium still has a strong appeal for young filmmakers. All over the world, micro-labs and micro-cinemas have sprung up, run by artist collectives dedicated to the preservation of analogue film. Kodak even launched a product that included a new Super-8 camera and new Super-8 films. Such a company calculates on profit and if they don’t see a market for it, they won’t do it, simple as that. Some studios in Hollywood still shoot on analogue film, only digital copies are shown in cinemas. This is due to the fact that analogue film lasts much longer than its digital version. The technology here is constantly changing and files need to be constantly migrated to remain readable on new devices. In many cases, this does not happen and films that are currently only produced digitally are lost forever within a short period of time. But the existing pool of analogue equipment is not always easy to maintain and preserve, and the prices of film materials and film copies have skyrocketed. I see this as a problem for independent artists like myself.

Should old analogue techniques be imitated with digital software or should new formal ways of dealing with digital film be sought?

No, one should not imitate old techniques with digital software. That would be parrot chatter. Artworks produced digitally should seek and experiment with their own unique possibilities, not imitate other media. This would be completely contrary to the modern understanding of art production.

You once complained that your films lose their material aspect (the fact that the films are made of film stock) when they are shown on the Internet. Specifically, you mentioned that certain films of yours may not be adequately displayed on platforms like YouTube. However, it is worth noting that in countries like Turkey, audiences can solely access your works through platforms such as MUBI, which may not align with your original artistic vision. In light of this, what message would you convey to these viewers, and what potential remedies do you envision? Do you believe there should be initiatives to establish spaces for traditional film projection, or do you acknowledge that despite the altered presentation of your films, audiences in these regions may appreciate a more intimate connection with your work?

I have made almost all my films available on DVD and digital platforms. This means that I don’t only work for the “lucky few” who have the chance to experience films on the big screen during film festivals or retrospectives. We all know most of the history of visual arts from art books and catalogues, not from direct museum visit. This is not possible anyway due to our limited life span. But when we look at a catalogue, we know that we are not looking at the work of art itself, but at a reproduction of it. And I ask everyone who watches my films on a screen to watch them with this background knowledge. It is not the thing itself and I don’t want them to forget that. And if one day the chance arises to experience one of my films in the cinema, they should take this opportunity.

Train Again (2021)

Let’s think about the latest film in your “Rushes Series”, Train Again (2021). How do you position this film in your series? Would you say that the cinema oeuvre presented by the other two films in the series continues this time “on the rails of the train” and with Kurt Kren as a companion, or would you say that this series has come to an end?

About 20 years ago, I was given several crates of rushes for a series of commercials. So original, uncut footage shot for various commercials, about six hours of material in total. The title “Rushes Series” implies that the film in question was fed in whole or in part from this pool. The film “Train Again” uses a few minutes of raw footage from the Austrian Federal Railways commercial I mentioned earlier. If I ever make another film that draws on this treasure trove, it will probably be another part of the “Rushes Series”. My next film, which does not yet have a title, wants to continue the tradition of futuristic filmmaking. The Italian and Russian Futurists were the first to realise the potential of the new medium and produced the first avant-garde films. In Italy in 1911 the brothers Arnaldo and Bruno Ginanni-Corradini produced some purely abstract films, in Russia in 1914 Vladimir Kasyanov with “Drama in the Futurists’ Cabaret No. 13”. This was followed in 1916 by the “Futurist Film Manifesto”. Unfortunately, almost all of these early films have been lost, but the film descriptions are available. In any case, I see the new film as part of a “Futurist Film Series” in which the basic concepts of Futurism, such as dynamics and synchronicity, will be visually realised. In fact, you can think of “Train Again” as the beginning of this series. In a way, the “series” only points to a possible continuity in my work in terms of my basic artistic concerns and their realisation.

The Exquisite Corpus (2015)

In your films, there is a tangible presence of the director who directly contacts the pelicle and makes them a part of the film. And this presence is not only behind the camera. For example, let’s think about the way you position the existence of the filmstrips as characters throughout your film The Exquisite Corpus (2015), or the diversity on the screen when we see the woman on the beach at the beginning of the film. When we look at the mechanical images of the film that you project in your film The Exquisite Corpus, can we, as viewers, feel that you are a fundamental element of the film?

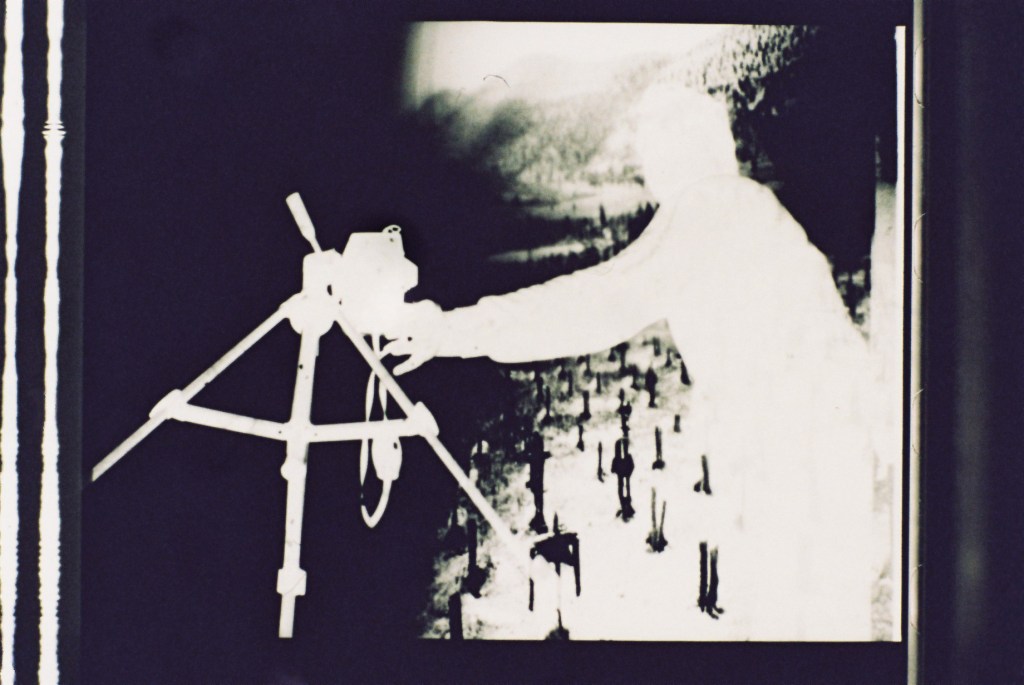

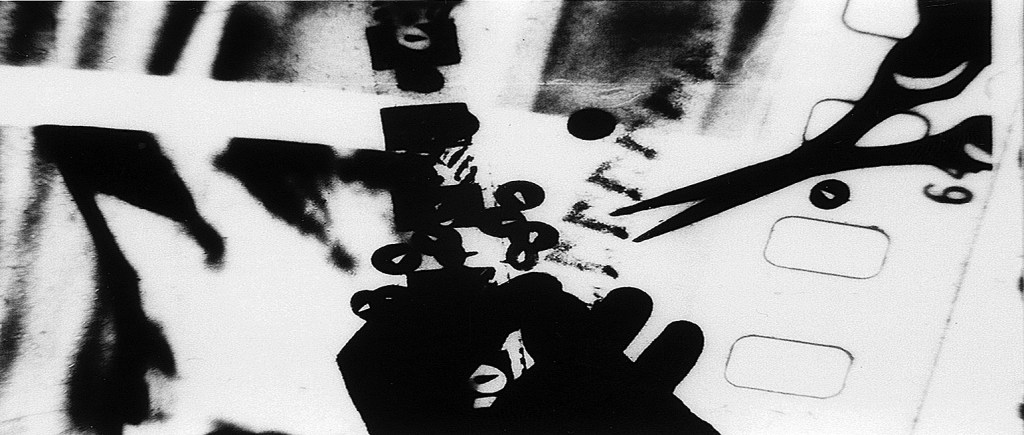

I see and experience every art form as a dialogue between the creator of the artwork and me as the viewer. The artist is always present in the work. Only in commercial films does the director seem to disappear behind his own images. This is a multi-layered issue that has been addressed by psychoanalytic film theorists, especially Christian Metz, and has been discussed in detail in theories such as “Screen Theory”. But this is not the case for avant-garde film, where, as in a work of visual art, literature or music, the artist is in constant dialogue with the viewer. And you are right, I try to further emphasise this state of the artist by making visible traces of my manual production process, so that we see not only the photomechanically produced images, but also their immediate processing, for example in “The Exquisite Corpus”, when I cut them lengthwise and then copy these strips side by side and let them move around in the image window. In this case, the act of cutting leaves traces of the artist and an indexical dimension is added to the iconic quality of the images. An indexical sign is one that leaves a trace. A footprint shows me that: Someone passed by here. And this indexical dimension is again something that can only be realised in analogue film, as Man Ray did in “Le retour à la raison” in 1923, by sprinkling objects on a strip of film and re-exposing them. When I put flowers and grasses on film and expose them, for example in the film “The Exquisite Corpus”, I leave their indexical traces. If I put them on a video tape, nothing happens. In “Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine”, I directly involved myself as an artist by letting my recordings interact with the protagonist. Or in “Dream Work”, when you see my hands, you see me holding and rotating the same film strip, while at the same time I touch and play the film strip projected simultaneously on the screen. Finally, I take a pair of scissors and cut the film strip, at which point the protagonist suddenly wakes up from his dream, looks up and starts laughing, as if he is looking at me.

Dream Work (2001)

Virgil Widrich’s selection of your film solely based on the film frames he observed, without any prior knowledge, serves as a commendable homage to your work. Numerous spectators, including Widrich, acknowledge and appreciate your distinctive filmmaking style that you have cultivated over the years. Even with just a single exposure to your films, the audience can discern and comprehend your unique cinematic language to some degree. What factors contributed to your comprehension of cinema and what motivated you to embrace this particular approach?

If I am asked to give advice to aspiring artists, I always say: Find your own language! Develop a distinct language that is all your own, that you can best express yourself in, that makes you and your work instantly recognisable and unique. Of course, this is easy to say and difficult to realise in practice, but this is the biggest challenge of producing art. For example, I learnt the darkroom technique at the age of 14 and developed my own negatives and photographs, so I already knew the technique, and when I came across two short advertising films in 1985, I had the idea to radically redesign them using contact copying. The result was my film “Manufraktur”. Twelve years later, I found a trailer for Terence Young’s historical film “Mayerling” at a flea market, and when I opened it and turned it 180 degrees to look at the footage, I immediately saw the Lumière brothers’ train arriving at the station in La Ciotat in 1895. This simultaneously gave me the idea for the film “L’Arrivée”, where not only the train arrives, but also the filmstrip arrives, slowly sliding from the right into the picture window, and on the filmstrip is the train, the train arriving at the station, and inside the train is a beautiful woman coming out of the train as the third arrival. In order to realise this idea, i.e. to make the film strip itself visible, my manual contact copying technique was of course ideally suited, especially through the perforation holes and the light tone.

Immediately afterwards, I wanted to make a film in which the film material itself would play a leading role, especially by making it visible through the perforations and optical sound. This was the idea for “Outer Space”; this is the “outer space” of the film strip – the area with the perforations and optical sound strips. For this, manual hand copying was perfectly suited.

L’arrivée (1999)

In an interview, you mentioned that P. Adams Sitney’s lectures at the Austrian Film Museum gave you the courage and enthusiasm to pursue filmmaking. This inspired you to move to Berlin, buy a Super 8 camera, and start making films. What kind of excitement can motivate a young filmmaker or someone hesitant about entering the world of cinema after reading your interview?

My passion for films and the magic of cinema started in my childhood, but back then, I never thought I could make films myself. I initially wanted to pursue writing, but soon realized I lacked the talent for it. It was only when I discovered avant-garde film through P. Adams Sitney that I saw the potential to create films as a visual artist. In 1978, without internet or widespread access to avant-garde cinema, the Austrian Film Museum hosted P. Adams to showcase New American Cinema for five days. By chance, I stumbled upon these screenings and was amazed by the possibilities of filmmaking. Just like my unplanned trip to Berlin, where I ended up staying for five years, and it was only in Berlin that I was able to develop as a film artist. Vienna wouldn’t have provided the same opportunities. Reflecting on my journey, I can’t help but marvel at the series of fortunate coincidences that shaped my life.

Peter Tscherkassky and P. Adams Sitney (Photo by: Eve Heller)

This is the first time your interview will be published in Turkey, and we are very excited about this meeting. Finally, we would like to hear what you would like to say to the cinema audiences in Turkey and the readers of Othon Cinema.

Yes, I have a small request. My great-grandfather Joseph Tscherkassky, who worked as a lawyer in Istanbul, Constantinople, also worked for the Sultan and died there. His widow, who praised the beauty of Constantinople to the end of her life, emigrated to Austria with her three children, including my grandfather, for various reasons. My great-grandfather was buried in one of the Princes’ Islands. I would be very grateful if someone could find his grave and let me know where it is. I would love to visit it!

Thank you for all your answers, it is very valuable for us to realise this interview with you. Goodbye until another day when we can talk about cinema at length.

Interview: Enes Serenli, Mert Babacan, Matthias Kyska, Hasan Doğuyel

Translation: Keda Bakış